So far we have seen how to identify Nodes in a P2P network, yet it is still unclear how Nodes actually communicate between each other. There are many different ways to achieve this. Over the next two sections, we will be focusing on how the Chord and Kademlia algorithms can be used for this very purpose.

Since Kademlia is a modified version of Chord, we will only be exploring Chord in this context, in particular regarding how Nodes determine which other Nodes to connect to. We will therefore not be diving into a full explanation of the original Chord paper.

Discoverability

Given a network of arbitrary, growing size, we are trying to find a way to communicate efficiently from one end of the network to the other. Suppose we have a starting Node S and a destination Node D: this means that starting from S, we are trying to find the quickest viable path to D. We can formulate the following constraints:

The path from S to D should be traversable in the smallest amount of steps, or network jumps. A network jump is when two Nodes connect to each other.

Finding this path should be very fast. There is no point in finding an optimal path if the time it takes to find it is much slower than the time it takes to traverse the path itself.

Steps [1.] and [2.] should maintain the properties of decentralization of P2P. This means that we cannot rely on a centralized server which is responsible for keeping an overview of the state of the network.

Why is this hard? Can't we just directly connect our starting Node S to it's destination Node D? While that might be possible, it is not always the case. This is because there is no central entity keeping track of all the Nodes in the Network.

Importantly, it is not feasible for every Node to keep track of every other Node, as this would mean that whenever a new Node enters the network it would have to update all other Nodes. The number of updates required for this to function grows linearly, making this approach not scalable, meaning it is not feasible at a large scale.

In a P2P network, each Node can only keep a partial map of the network at large, as keeping an up-to-date map of the entire network would grow too costly over time. Discoverability is the process by which Nodes use this partial map to connect to neighboring Nodes, which in turn try to get closer to the required destination.

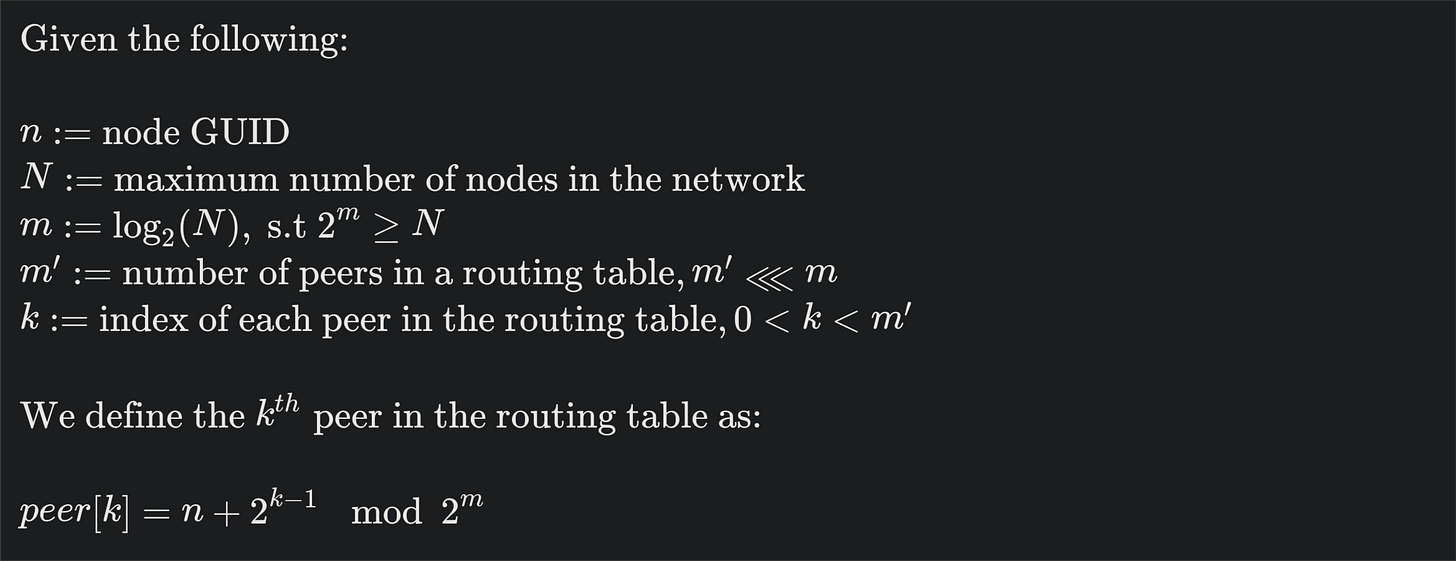

Routing Tables

Due to constraints in keeping an up-to-date map of the network, Nodes can only keep track of a small set of neighbors. Chord (as far as we will see here) is an algorithm for determining which Nodes in the network make up these neighbors (hereafter referred to as peers). These peers are organized together into a routing table, which can be seen as a sort of imperfect map of the network. This map can then be used to try and get closer to the target destination.

Let's break this down step by step:

Every Node in the network is keeping track of at most m' other peers. This value is chosen experimentally: the higher the value of m', the faster it will be for Nodes to communicate between each other, but the slower it will be for new Nodes to enter the network. A high value of m' also risks congesting the network by flooding it with too many messages.

Nodes keep as peers the Nodes which are closest to them in Keyspace. In fact, the distance between peers doubles each time. This means Nodes know more about the state of the network immediately around them, but are also able to connect to more distant Nodes if the destination is far away from them.

Essentially, this formula is creating a vague map of the network which mostly focuses on the local landscape, but with the mountains in the background in case it is ever needed to reach them. If you need more information, you can ask other Nodes along the way, as we will be seeing.

As we can see in Fig. 1, Node 0 is aware of Nodes 1, 2 and 4 as peers. It is not aware of any other Node in the network and cannot reach them directly.

Fig. 2 expands this view by showing the peers of Nodes 0, 1 and 2. Notice how all together these Nodes can now connect to Nodes 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 (we assume connections go both ways).

For a Node S to reach a target destination D, we apply the following algorithm:

If D is part of S's routing table, then S can reach the target destination immediately.

If D is not part of S's routing table, then we perform a network jump to the next Node in S's routing table which is closest to D.

We repeat step [2.] until D is part of the routing table of the current node, at which point we can jump directly to it.

Using this algorithm, it can be proved that, starting at any node, it will take at most log(n) jumps to reach any other node in the network, where n is the total number of nodes in the network.

Fig. 3 illustrates a practical example of this algorithm:

Starting at Node 0, we want to reach Node 3.

Node 3 is not part of Node 0's peers, so we jump to the next closest Node in its routing table, Node 2.

Node 3 is part of Node 2's peers, so we can jump to it directly.

In this way, we were able to reach Node 3 starting at Node 0 in only 2 network jumps, even if Node 3 is not part of Node 0's peers.

Joining a P2P Network

So far we have seen how a Node can reach any target destination in the Network with only a limited number of peers in its routing table. This however assumes a static network. How do we handle the case where new Nodes need to join? For this we need to introduce a new concept: Boot Nodes.

A Boot Node is a Node which is listed publicly (for example on the internet), to which new Nodes can connect to when joining a network for the first time.

This does not break the condition that no Node can have greater power over the network, as any Node can choose to become a Boot Node.

When a new Node N connects to a Boot Node B for the first time, it copies B's routing table. This is not ideal however, as B does not have the same GUID as N, and so it's routing table will not match. N will then use this routing table to connect to other Nodes throughout the network and establish contact with its peers so as to create it's own routing table.

It is as if you started a journey with no map, so you go to the nearest stranger and ask him for a copy of theirs. It still isn't a perfect fit but it is a good starting point: you use it to go around and talk to other strangers and copy parts of their maps until you have the map that is best suited to your journey.

The actual process is a bit more involved, as it might result in updating the routing tables of other Nodes, but this will be discussed in greater details in the next section on Kademlia.

Acknowledgements

This series is largely based on the lectures of Joshy Orndorff during wave 5 of the Polkadot Blockchain Academy in Singapore. You can find him on twitter at @joshyorndorff.

About the author & potential conflicts of interest

I am a graduate of the Polkadot Blockchain Academy, or PBA, which was hosted and paid for by the Polkadot treasury. I have prior experience in writing Blockchain Node software for the Starknet ecosystem.

This series might receive funding from external sources and if that is the case, it will be made explicit. This series does not aim to endorse or condone Polkadot or any other blockchain (such as Ethereum or Bitcoin) but where relevant might point out perceived advantages / disadvantages in technology between such networks.

Finally, since this series is written from the perspective of one more familiar with Polkadot and Ethereum, it will naturally touch more on aspects of these networks as compared to others.